Whatever media you work with – scores and parts, lead sheets or chord charts, lyric sheets, audio demo and reference recordings, DAW files, handwritten sketches – you’re going to generate a lot of information that you will want to keep track of. Your work is too important to lose. You should think about your specific work habits and needs, and develop a systematic way to organize your work files. When you think about a lifetime spent writing music, you’re going to generate a lot of material and you should make a plan that’s not too complicated and doesn’t take much time and energy to maintain. If you write a few things a month, that means you might write 200 things in the next 10 years. That’s a lot to keep track of.

Here are some thoughts about how to manage your various libraries over the long term. Depending on what kinds of things your write, you will generate files in one or more of these categories:

- Notation files (scores, parts, lead sheets, chord charts, lyric sheets, etc.) and miscellaneous files associated with the project (tune lists, budget spread sheets, credits, stage plots, concert information, etc.).

- Hard copies of scores, parts, lead sheets, etc.

- Stereo audio files of demos, rough mixes, final mixes, etc.

- DAW and ProTools files, which may include a lot of high quality audio and samples (meaning these are big files)

We’ll look at management of each of these file types, but first, I recommend creating a database of your work. It’s a little extra work to set up the first time, but once it’s done it’s a simple and easy process to keep it up to date. Information you want to capture includes: title, date written, performance date(s), instrumentation (there may be multiple versions for different ensembles), style, length, what larger project the piece may have been written for, and whether it’s been revised and when. There might be other things that you want to keep track of so you should customize to fit your needs.

notation files, miscellaneous files

Since these are relatively small files, you can probably keep your entire library of notation files on your computer and not worry about archiving files to keep disc space to a minimum. (Audio files are another matter.) Here are several recommendations for organizing these files.

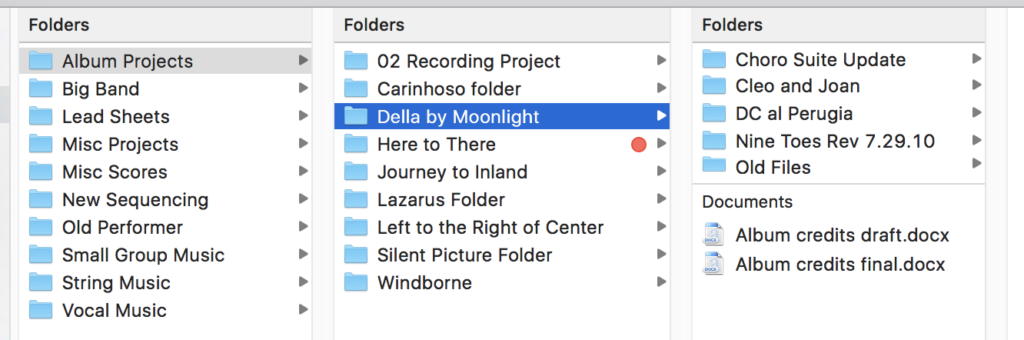

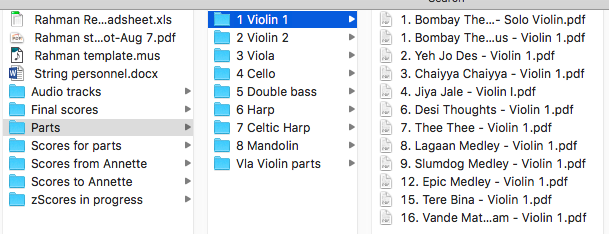

Organizing by project: when you’re doing a project that involves multiple pieces, such an album, EP, concert, tour, etc., store all these files together. That makes it easy to find all the files you’ll need for that project, and you’ll be able to go back later to the exact versions you used for that project. Here’s an example of how I have my album project files organized.

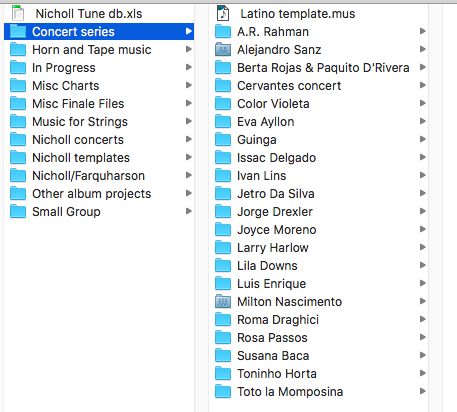

Here’s another example that shows how I manage files for a concert series I’ve been producing over the past several years:

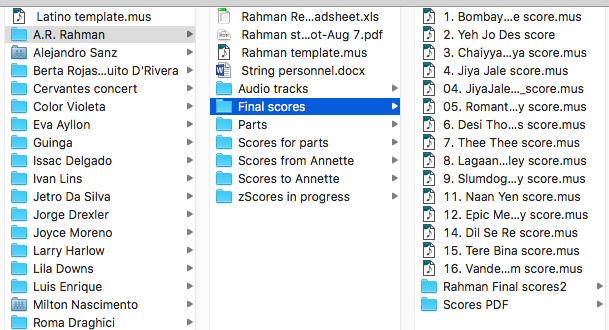

Within a project, it’s helpful to number the tunes. In the example below, I used the order of the concert to assign numbers to the pieces. That allows you to quickly scan the folder and see that there’s a score for each piece.

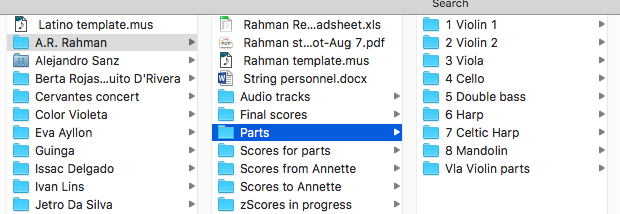

I also number the parts folders for each instrument in score order. This allows you to see at a glance if you have a folder for every instrument.

When the score has been numbered, the parts generated from it are also numbered. It’s easy to check each instrument folder to make sure there are parts for every player. (In the example below, not every piece has strings so there are no parts in the Violin 1 folder for charts 10, 11, 13, and 14. In some situations, you’ll want to make tacet parts for the players so that they have an empty part on the stand. That way, they know they don’t have a part on that tune.)

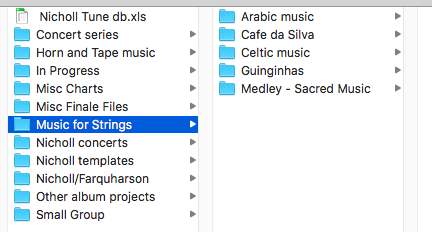

Individual pieces: you may do a lot of writing that’s not part of a larger project – a commission for an ensemble, an arrangement for a singer, a string arrangement for a piece, a demo for an artist or co-writer, a single tune for a show or concert, etc. One way to organize these files is to group them together into categories that make sense to you. In the example below, you can see I’ve created folders for Music for Strings, Misc Charts, Other album projects, and Small Group. Within each folder a simple alphabetical list works for me.

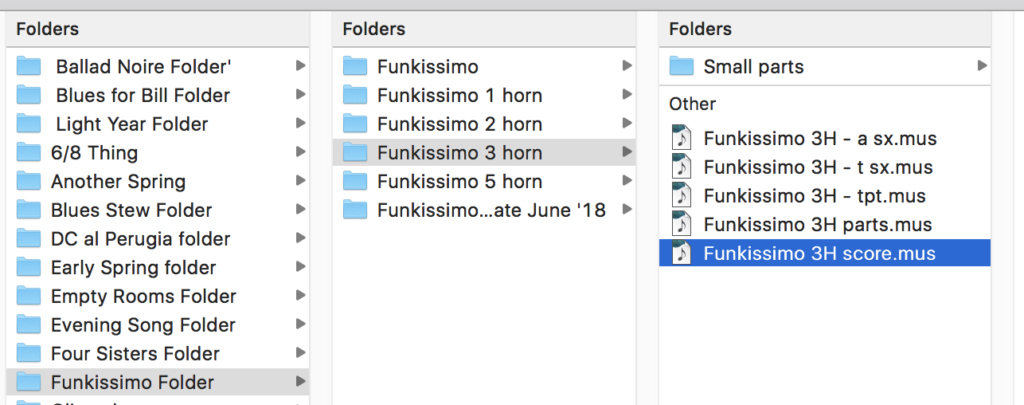

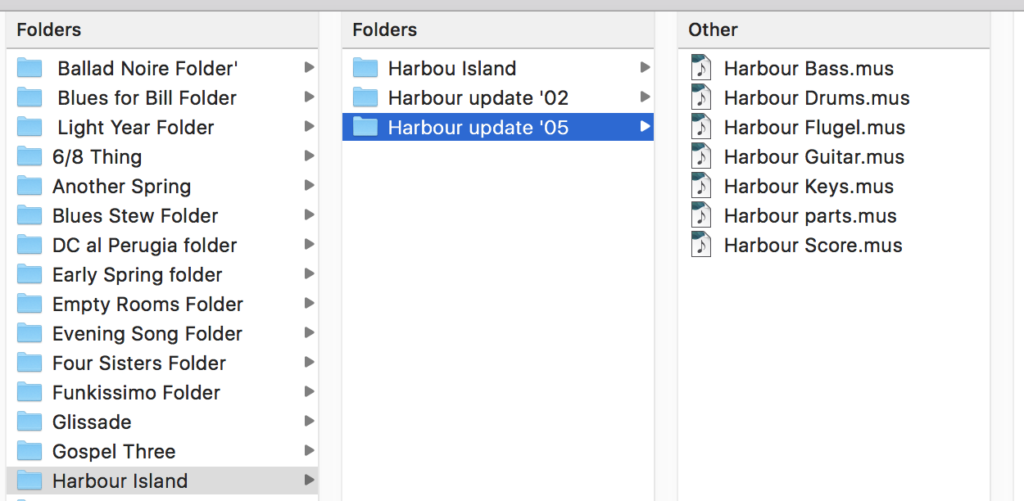

When I have multiple versions of a piece (for different instrumentations), I keep them all the same folder, named appropriately.

When I revise a piece, I’ve found the best thing to do is copy the entire folder and add the revision date to the folder name. That way, I have a copy of the original version of the piece in one folder, and all the revisions in another.

You should make PDFs of all your scores and parts and store them in your folders. It’s likely that your software will go through a number of revisions over the next few years or decades, or – heaven forbid – go out of business and you don’t want to lose a piece because you can’t open the file. At least if you have PDFs you can reconstruct the score, if necessary.

Currently, I have five versions of Finale on my computer, going back to 2011. I began using Finale in 1990 so I have hundreds of files that predate these versions. While successive generations are generally backward compatible, I have lots of files from the 90s that I can’t open with any of my versions of Finale. In a perfect world, when you get an update to your software you would go through all your files and save them with the newest version of your program. However, that’s a massive undertaking and I’ve never been able to find the time to do it. What I usually do is go through those pieces that are “active” (in the sense that I’m still performing them or having them performed) and make sure I can open them.

It takes time, energy, and a certain amount of discipline to keep your files organized, particularly when you’re in the middle of a project or two and you’re working to deadlines. File management is one of those things that not particularly fun or creative, but it pays off in the long run. Sometimes, when I’m in the middle of a writing session and feel blocked, I’ll take a quick break and do a quick sweep through my files and make a few tweaks.

It should go without saying that you should have a backup scheme for your computer files so that you don’t need to worry about losing any of your work.

In addition to notation files, you’ll often generate other files of budgets, concert programs, stage plots, riders, etc. Since these are small files, these files are easy to deal with. Just create an “other files” folder for the project or tune and keep them with your notation files.

hard copies

If you work with printed scores and parts for rehearsal, recording sessions, or performances, you’ll generate a lot of paper. Organizing and storing all this material is a daunting task. There are so many variables that dealing with hard copies of your work is something you need to figure out for yourself. However, I have a few suggestions that you might find helpful.

Store your files in stackable storage boxes, and pick the kind of boxes that have handles and are easy to move around. Label the boxes in some way that makes sense to you. When you’re searching through your files, you want to be able to quickly find the box you want, and if you ever move your house or studio, you don’t want to have to repack your materials. I have five boxes that I’ve had for years. One box has all my big band scores and parts, two boxes are organized alphabetically by title, and the last two have project folders. For projects, I like to use those old-school, brown accordion file folders with pockets so that I can separate the files either by instrument or by tune. My orchestral scores are stored in a closet in a big stack – not ideal, but it’s the best I can do.

When I finished the Carinhoso project (see Scores and Recordings), I had many, many files. There are nine pieces on the record, each piece has three scores (one 10×13 score for the original performance with the Israeli chamber orchestra, one 11×17 score for conducting the recording sessions, and an 8.5×11 score to use in the control room during mixing), individual parts for the rhythm section, wind players, vocal, and sax soloist, and multiple parts for the string players. I keep all these hard copies in case there’s another opportunity to perform the music live. Printing, binding, and collating all the parts took a great deal of time and I don’t want to do it again. Currently, all these scores and parts are in stacks on my piano. At some point, I’ll get a box just for this project.

For pieces that I perform often, I often email the players PDFs of their parts, but I also make sure to bring hard copies to rehearsal. Since I often tweak and update the charts depending on the situation, I need to be sure everyone has right version of each tune. So, rather than keeping hard copies of this repertoire, I usually recycle the parts after the concert or project. I do have a three ring binder of the most recent versions that I keep for myself, but if you have a lot of tunes and you’re performing them fairly often, you don’t want to try to keep track of multiple hard copies for every tune.

If you work in a similar way, you should consider adding a date to each part as a subtitle or somewhere on the title page. If you’re creating parts for a specific project, you could also add the project name as a subtitle. That way, you can tell at a glance what version of your piece you’re looking at.

stereo audio files

There are a lot of reasons why you might make audio files of your work. You might want to create demos to share with the players, conductors, concert promoters, etc.; playback of the score from your notation program to track your progress; mockups for your client; rough mixes of the tune in various stages during production; final mixes for review with your project team; and mastered final mixes to check before duplication.

The issue here, like the DAW production files we’ll consider next, is file size. To refer again to the Carinhoso project, we made stereo bounces of each of the nine tunes at each stage of the production. So for each of the nine tunes, we have: rhythm track rough mixes; rhythm tracks with the strings; full ensemble tracks (rhythm tracks with strings and winds); full ensemble with sax solos; full ensemble with vocals; rough mixes of the completed tracks; pre-master final mixes; final mastered versions. So that’s stereo mixes of 72 tracks (there were actually more as we revised and refined the mixes).

My solution was this: for all the tracks except for the final mixes and mastered final mixes, I kept the files in Mp3 format. This is not ideal sonically, but the purpose of these tracks was to check musical and certain production aspects that weren’t affected by the file format. Since I have an iPod that I use as my portable listening device, this enabled me to create iTunes playlists for each step in the production, an important way to manage all these tracks. So we either bounced the rough track as an Mp3 or I converted the WAV file to Mp3 later.

For the final mixes and mastered finals, I left those as WAV files and listened to them in my studio or office. Once the CD was duplicated, I imported the tunes from the disc as Mp3 files, but I also keep the final mastered mixes in my project folder. Once the project was finished, there wasn’t a strong reason to keep the roughs, but since I have plenty of room on my iPod and in my iTunes library, I haven’t deleted them. Sometimes I play these tracks for students when I’m talking about production.

DAW files

If you work includes tracking audio in ProTools or your Digital Audio Workstation (Logic, Cubase, Ableton Live, Digital Performer, etc.), you’re going to generate lots of audio files and each tune will occupy a lot of disc space on your computer. Hopefully, if you’re at the point in your writing career where you have these kinds of tools, you’ve given some thought about how to backup your files. It would be terrible to lose your hard work if your computer crashes or your files get corrupted.

Unlike advice about managing your other file libraries, as I wrote above, there are lots of tutorials and guides available, both from the software developers and from power users, about backup schemes. I strongly suggest you do your research.

There is one piece of advice that I think is worth considering: keep a detailed project log or your recorded production and update it as you proceed through the process. The information you want to capture is: the date of each session, location (home studio, pro studio, a friend’s production suite, etc.), the name of the project (if there is one), what piece you worked, and what – and who – you recorded. This information can really save you a lot of time and allow you to be sure you’re always working with the right files.

When Michael Farquharson and I were working on Left to the Right of Center, the project involved a number of sessions over the course of six years. We worked in fits and starts, and were interrupted often to work on other projects. We worked with three different harpists, two cellists, two percussionists, and recorded in several different studios. Because of the long time between some of these sessions, we had to go into the WAV files and look at the date they were recorded to be sure we were using the correct files. If you’re working on a project in a compressed period of time, to the exclusion of all else, you might remember the details of the sessions. But our work flow made that impossible. I kept a fairly detailed project log and that helped a lot as we were managing all the files over those six years.