Writing music is a process with many stages. How a writer proceeds through a particular project depends on a variety of factors, both internal and external. Experienced writers who know their own creative processes well will choose the best approach based on the circumstances of a particular situation. If they are writing in a style they know well, they might go right to score paper or their DAW and start writing. If it’s a style or ensemble they aren’t familiar with, they might do some research and extensive sketching in preparation. There are many different ways to work and an important part of a writer’s education is learning how to manage the process.

The experienced writer has this advantage over the beginning writer: they know themselves, their own strengths and weaknesses, how they work best in any given situation, how long their work should take, how much effort it will require, etc. All of this is part of the writer’s craft, as discussed in Chapter 1.

For a less experienced writer, many of these aspects are unknown. When novice writers begin, they are essentially discovering their own creative process through their writing. A teacher can be a great help by guiding the young writer, but there is no substitute for actually writing: writing itself is ultimately the best teacher. However, writers also need to be self-aware and develop a clear, complete understanding of how they work best and of the most appropriate process for any given project.

My own approach varies somewhat from project to project, but always contains several key elements. This process is the culmination of a long period of learning that began when I studied with several excellent writer/teachers in college, continued through a number of years of writing full-time for a living, and then underwent a process of further refinement when I started teaching.

Now let’s examine the stages and elements of the writing process.

(NOTE: As mentioned in the introduction, there are certain kinds of music writing for which the process described here does not – and should not – apply. In particular, the process through which songs are created for the highest level pop stars, like Beyonce, Rhianna, Lady Gaga, Khalid, Justin Bieber, and many others, has evolved well beyond the old-school, Tin Pan Alley process of the past where a single writer, or a composer and a lyricist, wrote the tune. It’s now common for a team of writers and producers – sometimes multiple teams – to collaborate in a variety of ways to create hit songs. While elements of the process described here can apply to this type of songwriting, I make no attempt to cover that process in this chapter. In addition, certain kinds of writing by composers working in the “classical” lineage fall outside of the process described here.)

getting started

The genesis of the music: why are you writing? There are many reasons to write. Sometimes a musical idea comes to you that is so compelling that it’s enough of a reason to write. At other times the musical seed idea comes later. In some instances, the motivation for writing comes from outside: you are commissioned to write a piece; you want to submit a piece to a competition and need to create an appropriate piece of music from scratch; a friend asks you to collaborate on a project; you’re preparing for a concert or recording and want to create some new music specifically for that project; you’re hired to write arrangements or original music for another artist; a director has hired you to score their film.

If the musical genesis of the piece is external, there’s a good chance that many of the decisions surrounding your work – its length, style, instrumentation, tempo, etc. – may already have been made. If the motivation is more internal, coming from a deeper, more personal musical motivation, a great many creative choices remain open.

Often, the reason you’re writing will determine your level of creativity or control over the final project. When you’re writing for a client (whether the client is your teacher, a producer, an ensemble’s conductor or music director, an artist, a record company, a film director, or an advertising executive), your work needs to fulfill your client’s expectations and must meet the specifications you’ve been given. This can be limiting creatively, but many writers thrive when working under such limitations. When you’re writing for yourself, you create the limitations under which to work. Many writers find this simultaneously liberating and frightening.

No matter which truth applies to a particular writing project, it’s important that the reasons for writing remain clear in your mind so that your work is on target and does what it should.

“Finding” or generating the initial musical seed ideas. This is the magical, mysterious part of the process. How you get the creative ideas flowing – find that initial germinal or seed idea that sets the whole process in motion – is often difficult to control with the rational, intentional part of our minds. Perhaps this is because the intellectual part of our mind really has nothing to do with this part of the process. Some other, deeper part of ourselves is involved with this stage of the work. How this happens is often very personal and is a measure of what we think our work means both personally and professionally.

Some writers like to get the process going by improvising on their instrument, others by setting up a groove with a sequencer and playing over it. Some like to walk outside and sing. Some writers merely turn their imagination loose and write whatever comes to their “inner ear.” For many, ideas come unbidden and present an opportunity to “seize the moment” and cultivate a germinal idea into a full-blown piece. Part of the writer’s craft is the self-knowledge of how to get the ideas to begin flowing.

I’ve found that the germinal idea from which the piece will grow also contains the energy that sustains the writing process . It’s as if the seed idea carries with it the necessary inspiration and energy that powers the creative process. I find the arrival of a germinal idea a mysterious but very encouraging event.

Making initial decisions. During the beginning part of the process, a number of decisions need to be made that set the boundaries of the work to come. Perhaps most important are decisions about who will play the piece, the instrumentation, the medium (live performance, recording), and the length. More detailed concerns would include the level of the players, the amount of available rehearsal time, the amount of studio time, the pre-production involved, the need for a demo or mock up, etc.

These decisions can also shape and channel the creative process through which your music is revealed. Once you’ve decided on the instrumentation of the ensemble, ideas begin to flow in the voices of those instruments. When you have a rough idea of the length of the piece, your musical ideas start to unfold with the right proportion to the whole and to each other.

working

Once the writing process has moved through the initial stage, the real work begins. This is the center and heart of the process, where ideas are discovered, shaped, and refined, where formal elements become clear, and the piece begins to emerge, grow, and develop.

Sketching. At some point, you need to start capturing the details of the music. Many writers begin working with the details of the music in a sketch. Much like the sketch a painter makes of his subject, you start sketching some of the details without worrying too much about perfection or completeness. Just get your ideas down quickly to fix their rough outline. Refinement comes later. I’m using the word sketching in the broadest sense of the word: not just through putting pencil to paper, but capturing a musical idea or gesture quickly, any way you can – through written notation, by recording audio, or by making a quick sequence in your DAW.

If you’re working with notation, the sketch could take a variety of written forms, from ideas quickly jotted down in a simple lead sheet to ideas roughed out in a full score. Songwriters may start writing lyrics in a notebook. Many writers use a DAW to make quick, rough audio sketches, or sing their ideas into the voice recorder on their phones. The point is that each writer should find the quickest and most accurate way to sketch their ideas, and that the sketching process should be easy, comfortable, and pose the fewest barriers to the creative process.

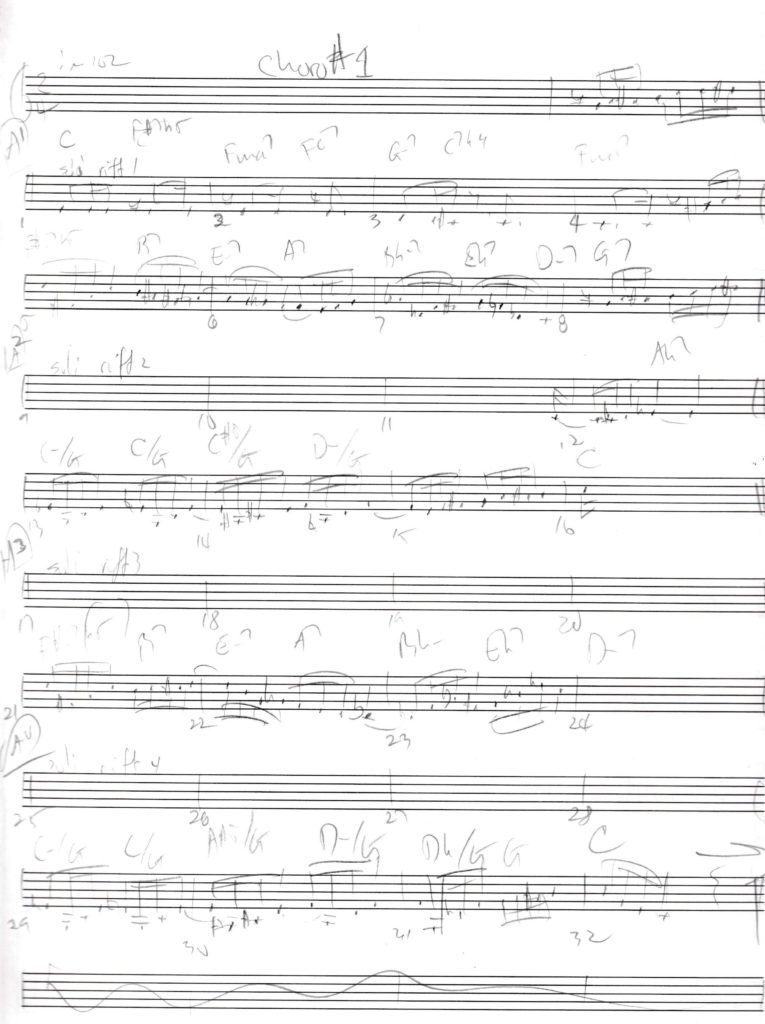

If you’re writing a simple tune, with a melody that will be supported by chords, a single-line sketch is fine. This would be appropriate for sketching out the lead sheet to a jazz tune or a song, or to quickly capture a piece in which the melody is the most important factor, even if it will be developed into a more complex piece later. I’ve filled dozens of spiral-bound notebooks of manuscript paper with simple, single-line sketches. Here’s the sketch I made working on the second movement of Choro Suite, a piece for woodwind quintet. In this case, the sketch was a way to quickly capture the melody/harmony for later scoring.

Example 1, Sketch of “Praça Onze” from Choro Suite

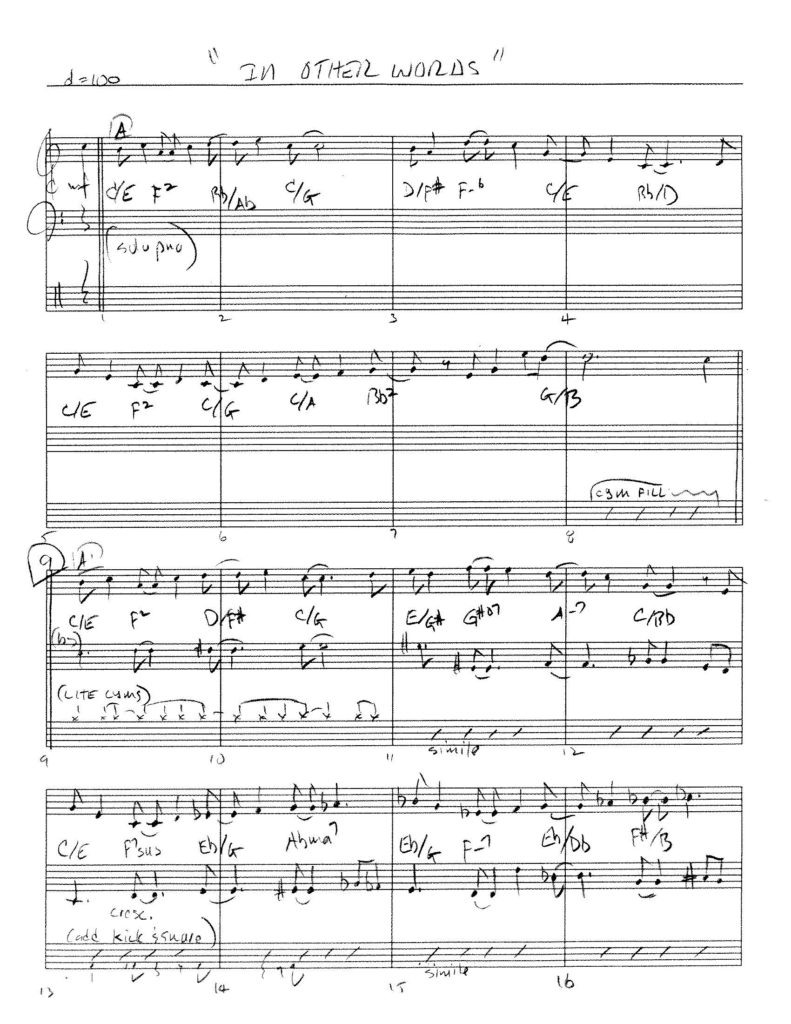

Almost anything can be sketched using three-line sketch paper. The sketch can include important melodies and lines, chords (either as changes or simple blocks), basslines, and maybe some rhythmic information. The layout of the sketch depends on the instrumentation and texture of the music. (I use three-line sketches extensively and created the layout of the page in Finale and had pads made at a local copy shop.) Here is an example of the three-line sketch for “In Other Words” that shows some linear, harmonic, and rhythmic ideas.

Example 2, The first page of the three-line sketch of “In Other Words”

When sketching, I tend to work very quickly and am not overly concerned with neatness and proper notation. The goal is to get the ideas down quickly, representing as accurately as possible the essence of my ideas. Because I’m usually the only one who sees the sketch, I feel that it’s OK if I use a lot of shortcuts and my notation is sloppy.

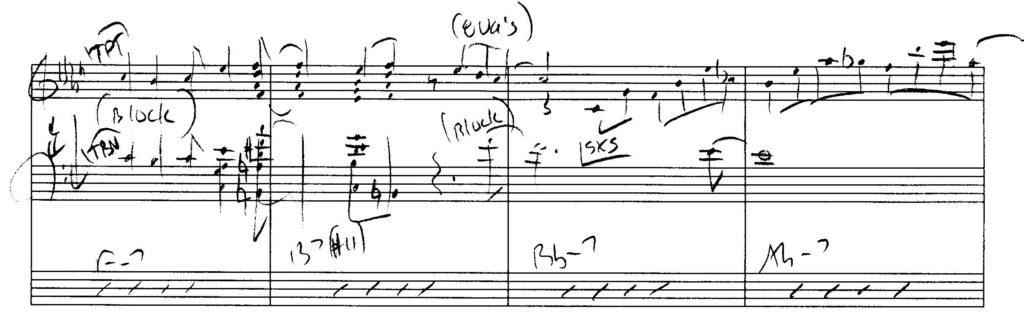

Here’s another example of a three-line sketch. This a single system of the sketch of is a piece for large jazz ensemble, “Blues for Bill Gidney.” Even though it shows the music for a 20-piece ensemble, it still fits on three-line sketch paper.

Example 3, A fragment of the sketch for the big band piece “Blues for Bill Gidney”

There are times, particularly when writing for for orchestra or other large ensembles, when four-, five-, or six-line sketches might work best. In other situations – writing for small group, for example – a lead sheet is all that’s needed. As you become more experienced, you’ll have a better idea which format to use.

Some writers skip the sketch and go directly to the score paper. The first draft of the score becomes a kind of sketch: they put in lead lines, jot notes about how things will be voiced, begin writing backgrounds, put in other basic information, etc. Later, they either clean up the score or create a second draft. Many writers are able to maintain the details of the piece on their minds, working things out without writing anything down. In this case, when they ultimately go to score paper, their work is more a process of transcribing what they’ve already worked out and “recorded” in their imagination. When and how to approach notating the initial ideas of a piece – and whether or not to create a sketch – is a personal choice that is an aspect of the writer’s craft.

In a similar way, writers using their DAW for sketching will often continue to refine and edit their initial sequence into the final tracks of the piece. The sketching process for a songwriter might involve making a demo recording that is either further refined into a more polished form, or they may choose to use the demo only for sketching and begin the production process in earnest once the tune has been written.

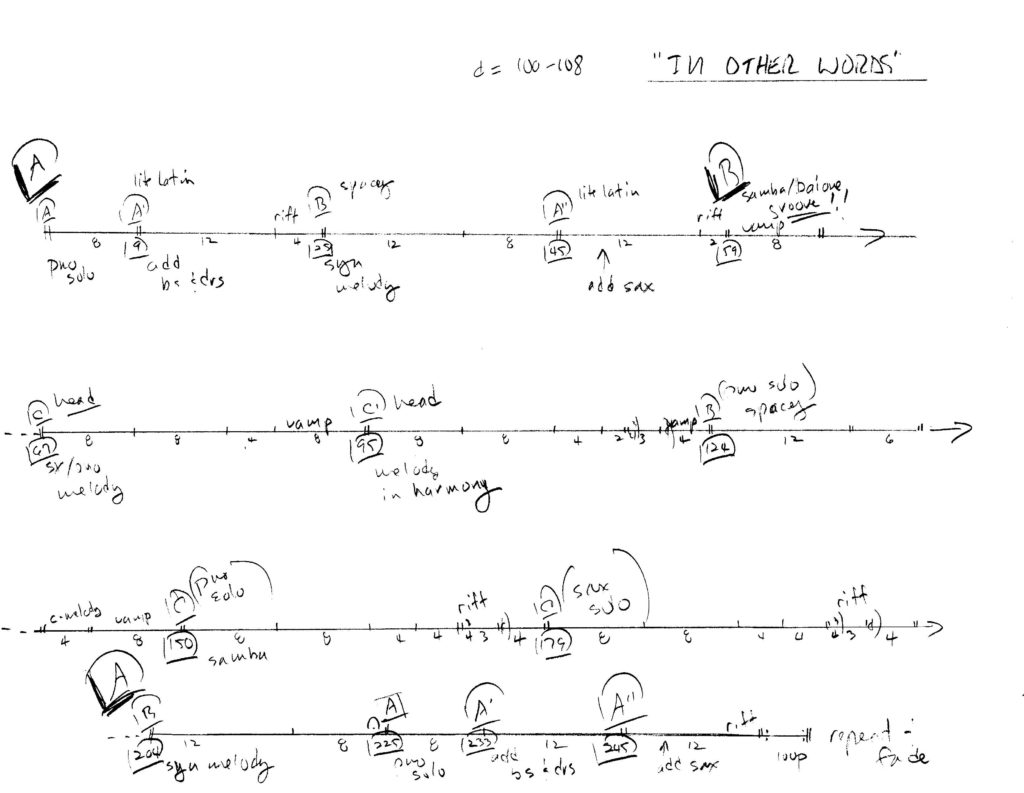

The schematic: shaping the form. Sketching involves notating the emerging details of the piece. Similarly, shaping the large-scale elements, such as form and dynamic contour, also occurs early in the writing process. Form can be notated graphically in what’s often called a schematic. A nice aspect of a schematic is that you can actually write it in real time: as you are imagining the piece unfold in time, you can be jotting down ideas as they occur to you. Using a simple timeline that graphically represents time going by, I fill in things like double bars showing sectional divisions, notes about orchestration, places where certain thematic ideas occur, and dynamics, solos, and other big-picture elements.

Here’s an example of the schematic to the “In Other Words,” the small piece mentioned above. This has been recopied to be more legible: like sketching, I tend to work very quickly when creating the schematic and the result is sometimes legible only to me.

Example 4, Schematic for “In Other Words”

Notice that the schematic shows the form using letter names and words to describe the sections of the piece. The standard dynamic symbols show rising and falling levels of energy. I also jot notes to myself (wherever they fit) about who’s playing what.

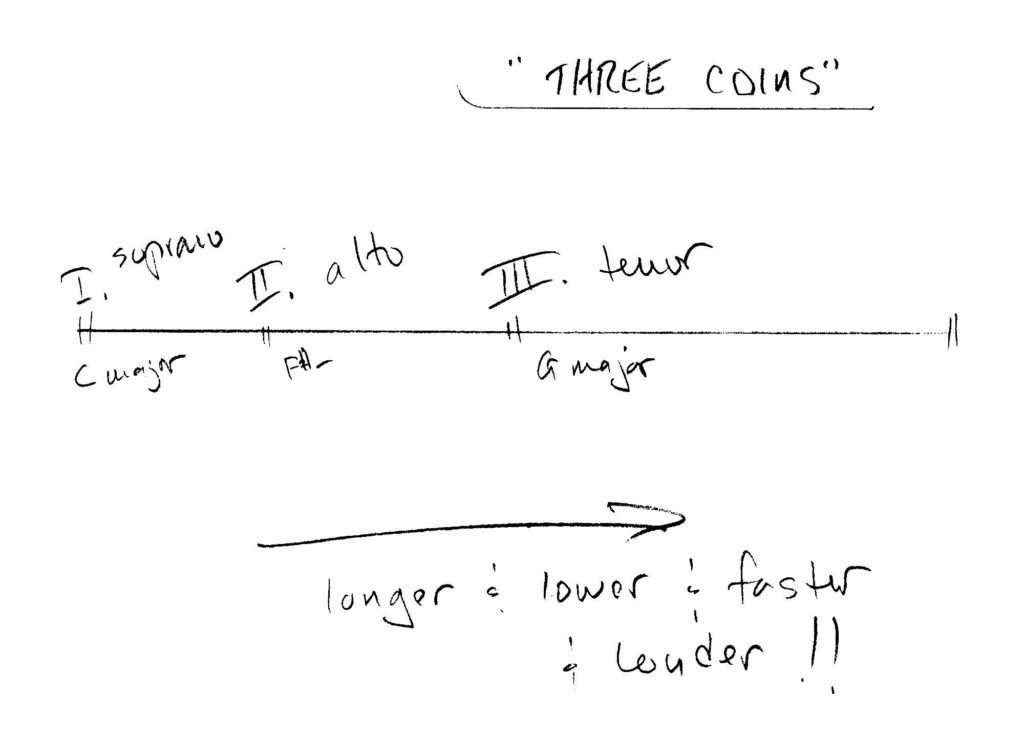

Here’s another sketch, this one showing just the basic structure of the piece. This is the first schematic I made for “Three Coins,” showing the three parts of the piece in very broad strokes. The piece is for saxophone and string orchestra, and my first concept was to use three saxes – soprano, alto, and tenor (the player I was writing for is adept at all saxes) – and have each section be longer and more intense than the previous one. Though this sketch took about two minutes to make, it contained essential large-scale aspects of the piece.

Example 5, Quick schematic of “Three Coins” for string orchestra and saxophone

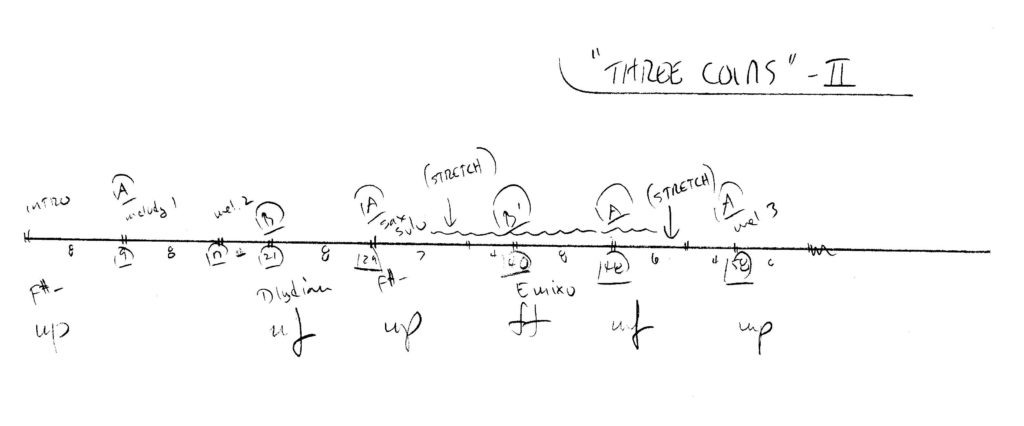

Here’s a more detailed schematic of the second section of the piece.

Example 6, Schematic of the second section of “Three Coins”

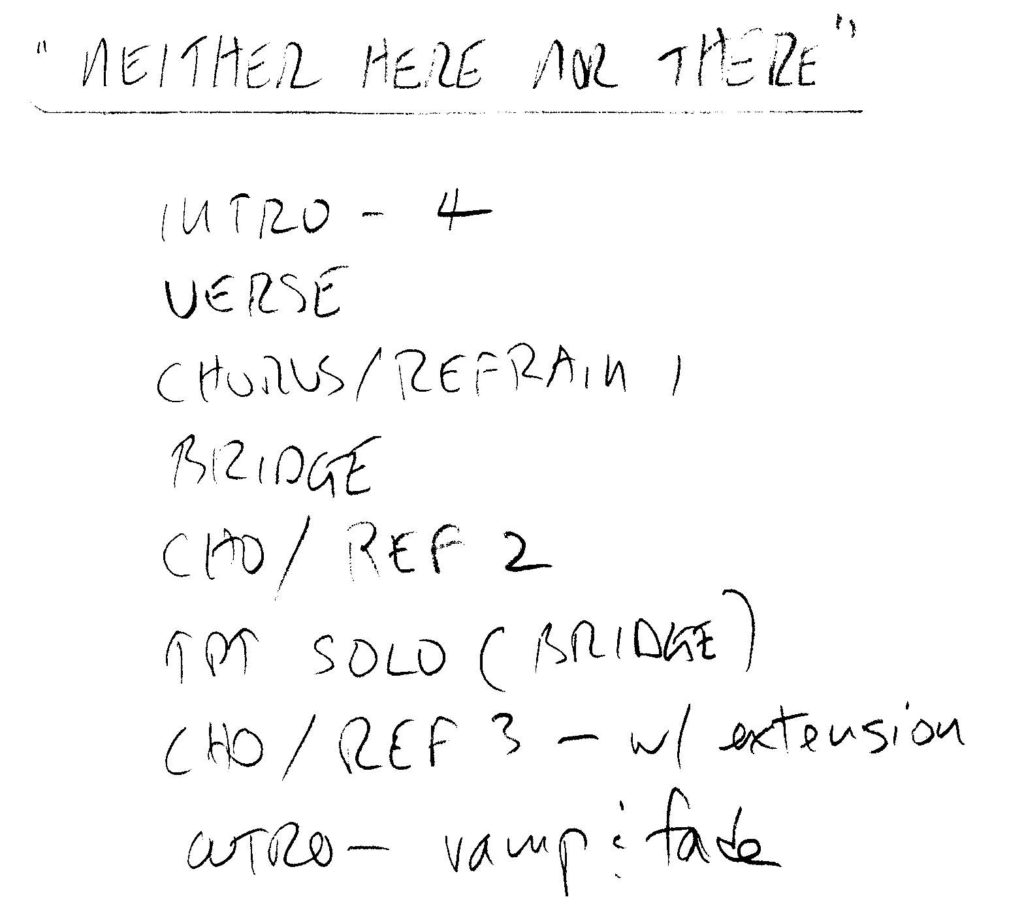

Many writers, particularly songwriters, work with the form by creating a list of the formal sections of the piece. While the schematic is a picture of the music, the list is a more literary approach to the form. The next example show a list of the sections of a song, following a fairly typical form, that I created for a tune I wrote called “Neither Here Nor There.”

Example 7, Form list for “Neither Here Nor There”

Whether you use a schematic or a list, or simply hold the form in your imagination while you score, is up to you. Pick the method that works best for the specific project. For a long, through-composed instrumental piece, a schematic might be the most effective way to deal with form. If you’re writing a song, a list of the song sections could be all you need. For a lengthy arrangement of a jazz standard for big band, a schematic can be useful to plan out your chart. When scoring a 30-second television spot or a short film cue, you can probably hold the formal elements in your imagination without needing any kind of schematic.

When sequencing or working in the audio domain, sketches might take the form of rough or demo tracks. Working with a DAW allows you to quickly and easily experiment with the form of the piece by cutting and pasting sections. Like working with a written sketch and schematic, the important concern here is developing the ability to quickly and accurately fix your ideas so they don’t get lost as you’re working. Waste as little time and effort as possible on the technical aspects (finding sounds, sequencing, recording audio, etc.) so that you can give free rein to your musical impulse as the music emerges from your imagination.

Cycling between the sketch and the schematic. During the writing process, these two elements – the sketch (details) and the schematic (form) – gain more and more detail as you make various decisions, and you’ll go back and forth between the sketch and schematic as you work out the small- and large-scale aspects of your piece.

As you progress through the writing process and approach the end of your work, the form of the piece and its contents become more clearly and completely defined. Gradually, the sketch and schematic fuse to represent the same thing: the finished piece. However, the sketch and schematic are abandoned when they’ve served their purpose and it’s time to make the final draft of your piece – whether it’s in a score, a sequence, or an audio recording. Sometimes (often, in fact), they are never actually fully completed, since their final form isn’t important. They are merely a means to an end and, unlike the score, are often never seen by anyone other than the writer.

Refining and developing ideas. Much of the writer’s work is refining, developing, and transforming the ideas that come during the sketching process. It’s not at all uncommon for many of the ideas generated during the early part of the writing process to be ultimately edited out of the piece. And that’s how it should be. The creative and sketching phases should generate as many different ideas as possible, leaving the judgments of the critical ear until later.

As we “work” our ideas, our craft, and particularly our critical thinking skills, becomes increasingly important. Now we are concerned with the development, the use, and re-use of material. We use our judgment about how to balance all the various elements in the piece. We’re still guided by our artistry, but we’re also using our experience, knowledge, and analytic skills to help shape the musical impulse. Working the piece should happen constantly right up to the final version of the piece. Always make time in the writing process to improve your ideas.

finishing

At a certain point, late in the writing process, your work reaches the stage where it’s basically complete. You’ve assembled all the musical ideas, the structure has taken its final form, and your big decisions have been made. At this point, you begin finishing the piece. I use the word in the sense that a woodworker finishes a piece of furniture or cabinetry – sanding the rough edges, applying stain or varnish, attaching any hardware such as handles or feet. These are essentially the final touches you make to complete the work.

Finalizing choices and fixing ideas. It’s common during the writing process that we leave important choices and decisions until later. Sometimes, we just can’t decide between all the possible choices. Other times, we’re waiting for inspiration to make those choices, or come up with other possibilities. Whatever the case, when we get near the end of the writing process, we can’t delay these choices anymore and need to make them so we can complete the piece. If we reach this point and still have doubts or lack confidence, this is the time when we often have to rely most heavily on our craft. If we feel depleted creatively, uninspired, or lack confidence, we should be able to assess the situation, understand the possible choices, and make an informed and technically effective decision. Hopefully, if we manage our time and energy effectively, we don’t run out of creative inspiration before the end.

Adding details. For a piece notated in a score, the details include dynamics, articulation, phrase markings, any text or directions written in the score, and all the last, little details that are necessary to its final preparation. In a sequence, this might mean adding appropriate controller data so govern dynamics and articulation, the relative balance of the tracks, any ambience added to the mix. For a songwriter, it could be the last little lyric tweaks to make the words as subtle or impactful as possible. These details are small, but they are important and the cumulative effect of getting them just right is essential to the effect and power of the music. This step could go relatively quickly, or it could take quite a bit of time.

Ending/stopping. If we’ve developed our craft and nurtured our creativity, we can reach the end of our work with a sense of accomplishment – with the confidence that we’ve written a good piece – and we stop because the piece is finished. In the best case, our creative inspiration and force of will last throughout the writing process and we finish the piece with energy and power to spare.

However, particularly when we’re writing for a client (a producer, a film director, an artist who has commissioned the piece) or are writing to meet a deadline, we don’t always finish fully inspired. There’s a great quote I’ve heard, attributed to the songwriter and bassist Sting. I don’t know if it’s something he actually said, but it contains a profound truth. The quote is about the mixing process, but it applies just as well to writing. He said, “You never finish a mix, you just abandon it.”

There’s a certain point you reach in writing a piece when you have to put your pencil down, save your file one more time, do a final bounce of the mix, or print the final draft of your score and say, “Alright, it’s done.” No more tweaking, no more final adjustments, no more doubts about the choices you’ve made – you’ve reached the end. Depending on circumstances, you may have another chance to finish your work through the process of revision…

Revising? Once the piece has been completed and been out in the world in some way, either in rehearsal, performance, or recording, you may feel there are things about it that still need work. You may decide to revisit the piece and rewrite or revise it in some way. If you feel the piece has enough value and may have more life in it (meaning there could be further performances or recordings of it) then revising is an option to consider. Depending on what you feel its flaws or weaknesses are, this could be a relatively small task. If there is substantial work to be done, it could be a longer, more involved process.

Sometimes it makes sense to leave a piece as it is and incorporate what you’ve learned from the experience into the next piece you write. Other times, your piece may be so close to your ideal that it would be a shame not to revise it. This is a very personal decision. The ability to easily revise scores and parts strongly argues for using a notation program like Finale or Sibelius.

Of course, if the piece’s final form is in a recording, that’s a whole different matter. Depending on exactly what’s being revised, you may or may not need to re-record the entire piece. A lot depends on the format and media of the piece.

Archiving. Many writers overlook this step. Once your work on the piece is finished and it has been performed, recorded, published, or otherwise released, it’s very important to keep all your work – including any hard copies as well as software files – in a safe, easily accessible place. This can be more difficult than it sounds, since hard copies of scores and parts are often over-size and don’t fit into many standard filing formats. If you’re working in the digital audio domain, you will generate many large files that take up quite a bit of hard disc space and you’ll want to carefully back up and store these files. If you’re working with a notation program, you’ll probably create several versions of the score and numerous individual parts and you should save them as both notation files and PDFs. Like audio files, you should store the final versions of your notation files somewhere safe and back them up conscientiously. A later chapter discusses managing your libraries.